- Quakers Today by Friends Journal

- QuakerSpeak Podcast

- Thee Quaker Project

- Clearly Quaker Podcast

- The Seed: Conversations for Radical Hope (Pendle Hill podcast)

Peace & Social Justice

Conflict Transformation Resources

From New York YM: Conflict Transformation Resources

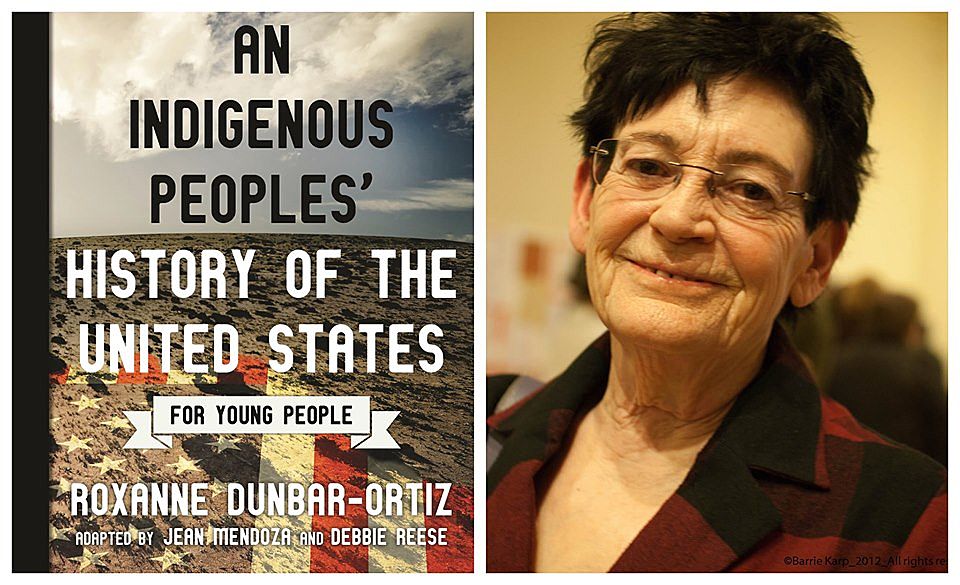

Choosing Excellent Children’s Books By & About American Indians

Freedom Means Podcast

Freedom Means – How to talk to young people about justice issues

The Freedom Means podcast is a thoughtful and engaging exploration of race, racial violence, and colonialism. Grace Aldrich and Emma Redden, the hosts of the podcast, use each episode to model what conversations about these complex topics could sound like. They role play different scenarios based on their own and listener’s experiences, and they offer insights and advice on how to talk to young people about these difficult issues.

One of the things I appreciate most about the Freedom Means podcast is the hosts’ willingness to be vulnerable. They share their own experiences of racism and white privilege, and they don’t shy away from talking about their own mistakes. This makes the podcast feel authentic and relatable, and it helps to create a safe space for listeners to explore their own thoughts and feelings about these topics.

Another thing I appreciate about the podcast is the hosts’ commitment to providing resources. They often end each episode with a list of books, articles, and websites that listeners can check out for more information. This is a great way to help listeners learn more about the topics that are discussed on the podcast, and it’s also a great way to support the work of other educators and activists.

Overall, I highly recommend the Freedom Means podcast to anyone who is interested in learning more about race, racial violence, and colonialism. The hosts are knowledgeable and insightful, and they create a safe and supportive space for listeners to explore these important topics.

Here are some of the things that I liked about the podcast:

- The hosts are thoughtful and engaging.

- The podcast is well-researched.

- The podcast provides resources for listeners.

- The podcast is a safe and supportive space for listeners to explore difficult topics.

Here are some of the things that I would like to see in future episodes:

- More discussion of the history of race and racism in the United States.

- More discussion of the experiences of people of color from different backgrounds.

- More discussion of how to challenge white supremacy in our own lives.

Overall, I think the Freedom Means podcast is a valuable resource for anyone who is interested in learning more about race, racial violence, and colonialism. I would highly recommend it to anyone who is looking for a thoughtful and engaging podcast on these important topics.

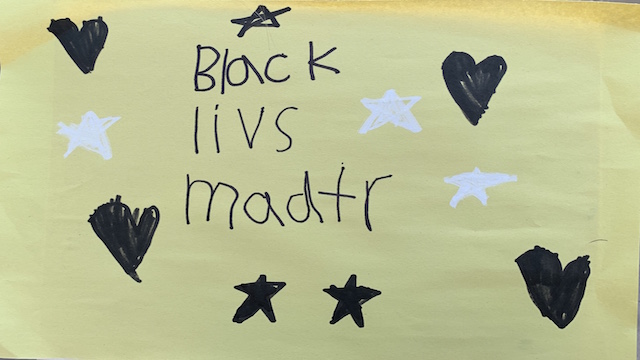

Racial Justice Curricula and Resources for Children

Talking with Children About Racism and Inclusion

- Talking About Racial Injustice with Children (a collection of resources for families and adults who work with children, June 2020)

- Talking to Children after Racial Incidents An interview with Howard Stevenson, a clinical psychologist at Penn Graduate School of Education.

- Table Talk: Family Conversations about Current Events Links to specific current events and guidance for parents, families, and caregivers. Also: Explaining the News to Our Kids on the Common Sense Media website.

- Coming Together: Talking to Children About Race and Identity Developmentally appropriate resources from Sesame Street for exploring racial justice and celebrating identity with young children. It’s Sesame Street, so there are songs, stories, activities, and familiar furry friends to help.

Resources for Anti-Racism Learning and Action

- Black Lives Matter Instructional Library (several books, across ages)

- Compiled by Pheobe Defino. An excellent collection of children’s racial justice books all in read-aloud format. Sections/shelves focusing on: Activism and Advocacy, Self-love and Empowerment, Black History, Libros en Espanol, Additional Resources and Contact.

- Children and Youth Resources Exploring Racism and Racial Justice (by Melinda Wenner Bradley, PYM) list of websites, blogs, online articles, curricula and children’s literature that begins with framing queries:

- How do we approach the work of teaching/learning about undoing racism for both Friends of European and African descent? Other People of Color?

- What scaffolding or tools can we create/recommend for working with a book resource? (queries, wondering questions, etc.)

- How do we prepare the way in our meetings and RE programs for ALL children to feel welcomed, included and fully participatory in the Religious Society of Friends? How do we signal welcome and inclusion to visitors?

- Racial Justice Curriculum for Young Friends (by Lisa Graustein, New England Yearly Meeting, for middle and high-school age Friends)

- “Something Happened in Our Town” — lesson based on a children’s story about racial injustice, told from two perspectives, that of a Black family and a white family. Created by Friends at Madison Meeting in Northern Yearly Meeting

- Protest Song Activity (created by the KidsBridge Center)

Native Justice

- Choosing Excellent Children’s Books By & About American Indians

created by the The Indian Affairs Committee of Salem Quarter, guidance for choosing books; there are many newer picture books which center the voices of Native people! - Children’s Books on Indigenous Residential Schools & Forced Assimilation:

- Art Activity for Remembrance and Healing for Native American Boarding Schools

- “Decolonizing Thanksgiving Is An Oxymoron – Kids Books Dismantling The Myth of a ‘First Thanksgiving’”

“Rethinking Thanksgiving” from Northstar Educational Explorations is a good resource for reexamining the holiday and history behind it to teach children the truth of Thanksgiving – modeling generosity and gratitude all year long – while remembering the violent history of colonization.

Why I am a Pacifist

If the pilgrim’s path is never easy, how does the pacifist fare? Tim Gee is a respected UK human rights activist and author of Counterpower: Making Change Happen (2011) and You Can’t Evict an Idea (2013). In this new book, a personal reflection of how he defines and interacts with the world as a pacifist, Gee continues his interrogation of strategies to win meaningful change without violence. Introductory remarks offer readers a short rudimentary history of the Religious Society of Friends and the principles for which it is known internationally.

In the first chapter the author evaluates his not-always-successful attempts to disengage himself from acts of physical and verbal violence during his early school years where teasing, forms of bullying, and peer pressure were present. Gee’s didactic tale invites readers to reflect on how they themselves might have reacted to similar school-day contests and the influence those formative years exerted later on their spiritual path toward pacifism. With respect to Quaker testimonies about peace, the labors of Margaret Fell, George Fox, and Sylvia Pankhurst are assayed, as are the Lamb’s War project and the stance of Martin Luther King Jr. and Bayard Rustin.

Gee argues that each one of us has a role in developing circumstances where peace can flourish.

Culture shapes language, which in turn shapes the way we think and the decisions we make. That we speak of ‘nonviolence’ reveals that within our culture, violence is the norm. We do not refer to war as ‘nonpeace’ . . . A commitment to peace encompasses a commitment to equality, economic justice and environmental protection.

While acknowledging that Quaker pacifism is rooted in spirituality, Gee contends that pacifism and the trials of the pacifist are misunderstood, i.e. pacifism is not a repudiation of conflict.

Subsequent chapters take up the evils of war and the many pathways to peace. To support his thesis that pacifism is active (not passive) work and that pacifists are earnestly engaged in challenging the prevailing stereotypes about pacifism, Gee draws on a variety of sources to demonstrate the effectiveness of nonviolent approaches to (re)solve world problems. In chapter 3, “Thou shalt not kill,” Gee debunks the “Just War Theory” that Thomas Aquinas updated and popularized in the thirteenth century and which is still invoked today. Since “a just war . . . implies God’s blessing,” Quakers seek the inner light and ponder what would Jesus do. Nonviolence, as reflected in the exemplary people power campaigns of Gandhi, Cesar Chavez, and Greenpeace, functions best when—through a structural critique—it devises a viable alternative to war and racial injustice: “To the extent that the use of nonviolent strategy did not result in everything the movement worked for, violent tactics did not achieve those objectives either.”

Even climate change, whose global effects are not distributed equally, signals “an intensification of the violence of inequality.” To his credit, Gee cites how nonviolent movements and Quakerism have been harmed by misogyny and a disregard for gender equality. While he does not equate pacifism with socialism, Gee asks us to consider that the mostly leftist leanings of pacifists do not translate into the left being singularly pacifist. The case of Quaker activist Nozizwe Madlala-Routledge’s membership in the African National Congress and South African Communist Party is illustrative of the political elasticity of pacifists who “can participate in movements that have both nonviolent and armed components.”

Following musings on genocidal crimes and the success rate of civil resistance worldwide, Gee serves up anecdotes (“But what would you do if . . .?”) about nonviolent stands that ordinary citizens (not necessarily declared pacifists) have taken victoriously to thwart acts of violence directed toward them. Gee concludes that the presence of God within directs his testimony and, through practice, paves the path for peace within us all. Pacifism, as a moral doctrine, and the principles that frame it are, for Gee, part and parcel of his non-negotiable spiritual journey.