Written by: Grace Sharples Cooke, Haverford Monthly Meeting

In her humorous cartoons about Quaker proclivities, cartoonist Signe Wilkinson (Chestnut Hill Meeting, PYM) highlights the sect’s inconsistencies. But she is not the first; Quakers have been the target of satirists since the mid-eighteenth century, after the first newspaper was published in the American colonies and satire had become common in England. In the colonies, it took the form of political cartoons or written jokes. There were four 18th and 19th century events in Pennsylvania that produced typical anti-Quaker satire.

Paxton’s War 1763 and the Election of 1764

The Paxton Boys murdered 20 Conestoga Indians to express their disapproval of the Quaker dominated-government, to make a political statement about their beliefs about race relations, and to seize Indian land. Following the massacre, a public debate unfolded (the 1764 pamphlet war) with more printed materials published than any time prior to 1763. The anti-Quaker pamphlets blamed pacifism for the failure of Quaker leaders in the Pennsylvania Assembly to defend western frontier from Indian attacks.

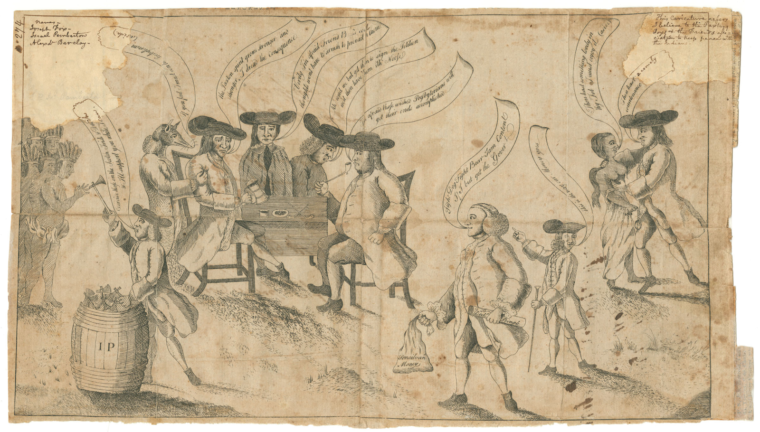

At the left side of the image above, Abel James, a prominent Quaker merchant, hands out tomahawks to Native Americans from a barrel labeled “I. P.” (for Israel Pemberton). At right, Israel Pemberton, a Quaker leader in the Pennsylvania provincial government, embraces a bare-chested Native American woman, who steals his pocket watch. In the middle of the scene, a group of four Quakers with sad faces, holding beer mugs and pipes, sit around a tavern table discussing the growth of “the Paxton spirit” in the frontier and the political influence of thePresbyterians.

Joseph Fox (depicted as a fox), a Quaker Assemblyman, stands to the left and remarks that if the Quakers’ plan fails he “must turn Presbyterian again.” In the middle-right foreground, a cheerful-looking Benjamin Franklin, holding a sack labeled “Pennsylvania money,” remarks that he will be content as long as he wins the election. He is followed by a man holding a staff and wearing a tri-cornered hat who points at Franklin, announcing “This is where our Money goes.” Quaker Pemberton (called King Wampum) had succeeded in negotiating the Treaty of Easton, in which the Pennsylvania government promised to respect the autonomy of Ohio country Indians in return for their cessation of attacks on settlements. But Indian attacks continued, and later increased with Pontiac’s War in 1763. Backcountry settlers—as well as many sympathizers in Philadelphia—increasingly regarded all native peoples as enemies, and the Quakers their abettors. They were also suspicious that plainness and claims about the inner light hid licentiousness.

Abolitionism 1830s

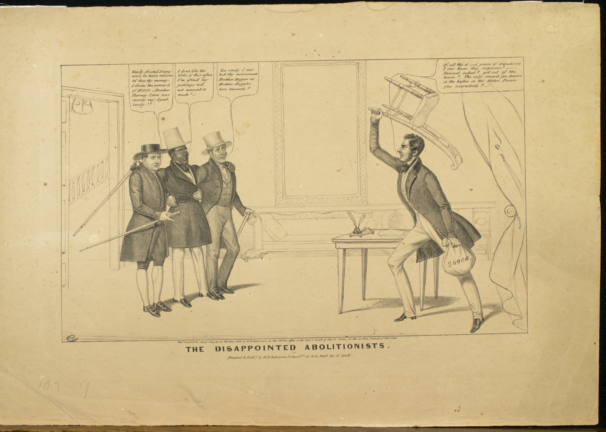

In this cartoon, Quaker Isaac Hopper says: “Verily friend Darg since we have returned thee thy money, I claim the reward of $1000. Brother Barney Corse was merely my Agent, verily!!” Black Man David Ruggles: “I don’t like the looks of this affair. I’m afraid my pickings will not amount to much!”

White Man Barney Corse (Quaker arbitrator): “Yea verily I was but thy instrument Brother Hopper as Brother Ruggles here knoweth! Man with a Chair: Of all the d—-d pieces of impudence I ever know, this surpasses! Reward indeed! Get out of the house! The only reward you deserve is the halter or the States Prison, you scoundrels!”

This case involved a fugitive slave of John Darg who stole $7000 from him, fled, and was harbored and assisted by African American abolitionist and writer David Ruggles, Quaker arbitrator Barney Corse, and Quaker abolitionist Isaac T. Hopper. Corse had arbitrated a deal with Darg that in exchange for the return of the stolen money, the slave’s freedom would be granted, and a small stipend would be paid to Corse. The arbitration was discovered and annulled by the New York police who then arrested Ruggles and Corse, although they eventually won the slave’s freedom. The illustrator seems to criticize the Quakers and Ruggles for their sudden timidity (and deal-making) when confronted by the slave owner.

The Compromise of 1850

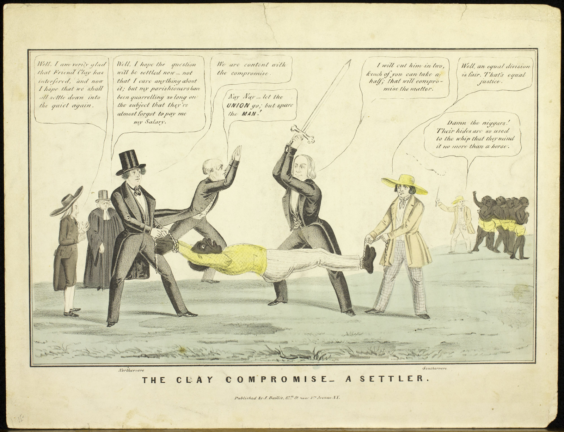

This cartoon satirizes Henry Clay’s Compromise of 1850 concerning the extension of slavery to the territories. It depicts a prostrate slave being pulled by ropes from each end by a Northerner and Southerner. The Northerner states, “We are content with the Compromise,” and the Southerner states, “An equal division is fair.” Standing over the slave is Henry Clay who is poised with a sword to cut the slave in two. William Lloyd Garrison rushes to stop Clay, stating “let the Union go; but spare the man!”

A Quaker confers with a minister about the compromise, saying “Well I’m very glad that Friend Clay has interfered and now I hope we shall all settle down into the quiet again.”The minister responds that he hopes the question is settled because his parishioners have been quarreling so long that they almost forgot to pay him. A slave overseer about to whip a group of slaves curses their ability to withstand the pain.

Civil War 1861

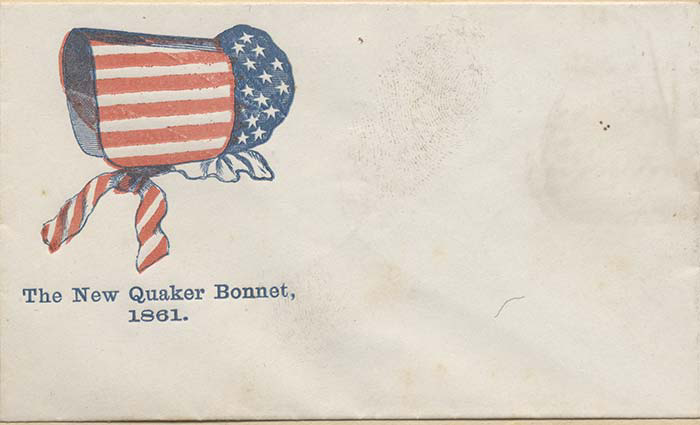

During the Civil War, cartoonists were more positive about Quakers but suggested that they would (or should) give up their pacifism for a more righteous cause-the war against slavery. Mailing envelopes with a patriotic position inscribed on them was popular. Here is one about Quakers: This particular envelope design reflects the popular image of a “fighting Quaker”, suggesting that plain dress was easily adapted to the necessary violence of the times.

Sources

- “The Clay Compromise: a Settler, 1850”. The Library Company of Philadelphia. Accessed May 12, 2021.

- Clay, Edward Williams. “The Disappointed Abolitionists”., 1838. Library of Congress. Accessed May 12, 2021

- Claypoole, James “Franklin and the Quakers”, 1764. Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

- The cartoonist is critical of the congressional bill that does not restrict slavery but allows it to spread in certain places and pays slave catchers who return slaves to their owners. Quakers are mocked for not standing up to the pro-slavery forces.

- In a “Harpers Weekly” joke published in 1861, the Quaker says to the Confederate: “Friend, I will not kill thee, but I will hold thy head underwater until the breath departs from thy body.” In an 1864 joke in a southern newspaper, a Quaker says to a Confederate gunner: “Friend, I counsel no bloodshed, but if it be thy design to hit the little man in the blue jacket, point thine engine three inches lower.” Reality sometimes demands a violent response, even from a pacifist!

- Throughout these historical satires of Quakers, there is a distrust of Friends’ claimed values, with pacifism a frequent target. Like many satires, incongruity is key to the image of the “fighting Quaker” which continues in modern cheers for the sports teams at some Quaker colleges: “Fight, fight, inner light! Kill, Quakers, kill! Knock ‘em down, beat ‘em senseless, do it til we reach consensus!

- Connerley, Jennifer. “FIGHTING QUAKERS: A JET BLACK WHITENESS.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 73, no. 4 (2006): 373-411. Accessed May 3, 2021.

- Fenton, Will. The Digital Paxson. Commonplace. Accessed May 3, 2021. h

- Mendoza, A.J. “Beyond the Oatmeal Box”. Friends Journal, August 1, 2014. Accessed September 23, 2021.

- “The New Quaker Bonnet”, 1864. Digital Georgetown. Accessed May 12, 2021.

- Olson, Alison. “The Pamphlet War over the Paxton Boys.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 123, no. 1/2 (1999): 31-55. Accessed May 3, 2021.

- Olson, Alison Gilbert. “Pennsylvania Satire Before the Stamp Act.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 68, no. 4 (2001): 507-32. Accessed May 4, 2021.