This profile is the first in a series of Q&A articles on Quakers in higher education.

Friends have had a deep impact on the practice and theory of instruction since the very early years of the faith. They also have complex personal interests and engage deeply in civic society. They have served as role models, scholarly advisors, and mentors to many individuals and students, but in so many Friends meetings and worship groups they are simply beloved builders of faith community.

Biographic Information

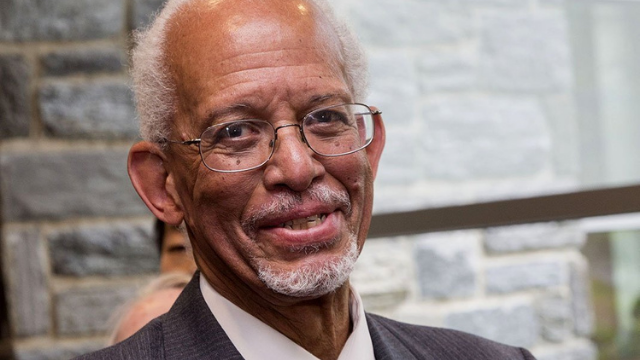

Maurice Eldridge is a retired Swarthmore College administrator and lifelong educator who serves as Assistant Clerk for Swarthmore Monthly Meeting and the Pendle Hill Board.

When you meet Maurice, you immediately notice a graceful warmth and courtesy. This is backed by a rich literary, humanistic, and cultural knowledge and a deep sensitivity to what is real, and what is not. To be near him is to feel a strong inner light.

A born thinker, Maurice received a bachelor’s degree in English literature from Swarthmore College in 1962 and a Master’s in Education from the University of Massachusetts. After years of teaching English and creative writing, he served as the assistant headmaster of the Windsor Mountain School in Lenox, Mass. He later became an education specialist with the Massachusetts Department of Education, followed by a 10-year role as principal and director of the Duke Ellington School of the Arts in Washington, D.C.

In 1989 Maurice returned to Swarthmore College. He spent 27 years in academic and community leadership roles before retiring from the position of Vice President for College and Community Relations in 2016. If you search Swarthmore College’s website their search engine reveals how great an impact he had on the college’s students – there are some 414 mentions of him, his work, and the way he carefully sowed wisdom and curiosity among the students he worked with.

Maurice Eldridge gave the 2009 Baccalaureate address at Swarthmore and it begins like this:

I was born 75 years after the Emancipation Proclamation in the sleepy, southern, segregated town you know as Washington, D.C. — our nation’s capital. My first and most powerful memory of an act of Jim Crow comes from the third year of my life there in my hometown.

The speech is iconic in its portrayal of the “there in plain view racism” that is embedded in our nation’s history and documents the lived experience of a whole generation of people of color born during and after WW II. It is a must read.

The subtleties of managing race as a brilliant, loved, child give way to stories about the experience of boarding school and college and adult life. All of it is a reminder that humanity is within us all, as is the capacity for faith, glory, error, cruelty, failure and redemption.

Q. How did you end up working as an educator? What led you to this job?

Choosing to become an educator occurred during my slow progression from the earlier stages of my life when, for instance around age 6, in the year that my paternal grandfather died, I thought I would grow up and become a Baptist minister like him. I loved hearing him preach and the music that poured from the choir. His death shook me, but on I went with my dream. As I continued the path through my education, my sense of the world grew with me. I went through a period in my teens when I decided to be an atheist and then I moved on to a level of thought in Swarthmore College that made me decide that was arrogant and so I became an agnostic.

In high school, I met my first Quaker at Windsor Mountain School where he, Peter Klopfer, had also gone to school. He was a Biologist and had been a conscientious objector during WW II, gone to jail for a while, and done community service the rest of the war. I admired him deeply and knowing his history helped me get through applying to be a CO too during the Viet Nam war. Had I been drafted I would have resisted.

Peter gave us students experience with learning about other religions, including Quakerism, and about Amish people and others of difference. His wonderful family was inspiring but I was, I guess, for a long time a closet Quaker and came out of that closet when I returned finally to work at Swarthmore and visited the Meeting. I took solace in it when my wife, mother of my two children, was dying from cancer. I was able to stay whole through the spirit of the Meeting and became a member (She was an Episcopal Church member – with beautiful music).

I go on too long.

What led me to become an educator was my deep admiration for my teachers, both in the public segregated junior high I attended in D.C. and in the very progressive integrated boarding school I went to in Lenox MA; the Windsor Mountain School. There I changed my path toward becoming a teacher. That determination helped define my life as a college student and kept me steady on that path.

An experience with racism at college put me in deep pain and led me to discover the strength that allowed me to become a teacher in and outside of the classroom when I took my first job teaching in a predominantly white school district. There I learned how to trust myself and to reach out to my students not only as their English teacher but also as a potential friend and possible guide and mentor in their lives beyond the classroom. This last bit has governed all of my life’s work with young people, with my fellow teachers, and the staff I eventually led at the Ellington School of the Arts in DC. (It governed) the various roles I filled at Swarthmore and the volunteer work I continue to do now in Chester PA and at Pendle Hill.

I believe that modeling is the strongest tool or skill in life and in educating. As Mahalia Jackson sings, “I am going to live the life I sing about in my song”.

What does being a Black Quaker mean to you?

Being a “black Quaker?”

My first thought is that the only race I believe in is the one we all share, the human race. Nevertheless, I know I am a Black American, African American, Negro, Person of Color, or whatever the beholder recognizes and believes.

What it does mean is that in many Quaker settings I am more often the only person of color present or one among a few. That needs to change in so many settings in our national and community lives. It means that I have work to do as a Black Quaker to help as I can to make diversity a reality in the various settings of my life.

I do it at will but I also find that at times I have to make room for others to do this work so that it is not the case always that it is seen as my responsibility…others must learn who they are more fully and do the work too.

Since you retired, what have you chosen to focus on?

I have chosen to continue the work I undertook while fully employed which was voluntary work, but work in the spirit of the College and a reflection of my values and my love of working with young people and with institutions that seek to make life better and rewarding for all.

I helped start the Chester Children’s Chorus over 25 years ago and serve presently as an emeritus member of its Board. I serve on the education committee, sometimes the governance committee, and always help with fundraising. I serve on the Board of the Chester Charter Scholars Academy (which started out named as Arts School); I was one of the founders of the school that grew out of the success of the Chorus. I also serve on the Board of Pendle Hill as Assistant Clerk; I am also Assistant Clerk of the Swarthmore Friends Meeting.

What do you feel you bring to the faith from your experiences as an educational leader at Swarthmore?

I think I bring with me both my desire to help fulfill the values and mission of the institution by sharing what I have learned in my career and in the spirit of my faith, my wish to share the Light of Love with all. I have at Swarthmore and before learned to listen well to others and to go beyond words and act out what I say.

I know that I can learn from others still and that is a part of who I want to be. I can critique mostly gently and take criticism with respect.

Given your background in community relations, what do you think Friends could do differently as they engage with the community?

The most important thing from my perspective is that we enter communities with open minds and the ability to convey to the members of the community that you are not there armed with answers to their needs.

You have to be a listener, a learner, one coming with humility to collaborate and cooperate, not to dictate, not to be judgmental but to ask questions to broaden your understanding of both the issues at play and the desires of the community.

If you could have all Friends read any two books, what would those books be?

“Go Tell It on the Mountain,” by James Baldwin.

“Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption,” by Bryan Stevenson.

This is Black History Month; do you have any suggested books, articles, practices, or resources for Quaker Meetings, worship groups, or Friends?

Fiction: “Kindred” by Octavia E. Butler: “Kindred” will rock you through the juxtaposed realities of slavery times and contemporary life by a compelling evocation of time travel.

“The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian” by Sherman Alexie: The Alexie novel will, with wit, humor, and honesty, invite deeper understanding of life as an indigenous person in what was once his homeland and his culture.

Non-Fiction: “The Fire Next Time: A New Generation Speaks about Race”*, Jesmyn Ward, Editor: This book offers a collection of essays that will help us find answers to the question asked below about Baldwin’s “The Fire Next Time”.

“American’s Original Sin: Racism, White Privilege, and the Bridge to a New America” by Jim Wallis: Jim Wallis’ title encapsulates his deeply thoughtful message.

“We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy” by Ta-Nehisi Coates: “Eight Years in Power” grabs hold hard of the Obama years and brings down the idea of a ‘post-racial’ America.

Set Two: Additional reading suggested as you have time and interest:

“You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me” – Memoir – by Sherman Alexie:

“Men We Reaped” – Memoir- by Jesmyn Ward: A powerful and painful journey of self-discovery through enduring and coming to terms with the deaths of five men in her life including her brother and in the life of their community.

“Locking up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America” by James Foreman Jr.

“Between the World and Me ( A letter to his son)” by Ta-Nehisi Coates

“Just Mercy” by Bryan Stevenson

“The New Jim Crow” by Michelle Alexander

Wouldn’t hurt to look back at James Baldwin’s “The Fire Next Time” asking ourselves how much-sustained change has there been in the more than five decades since this essay was first published.