Quaker education has always been grounded in basic principles of the Religious Society of Friends. Each child has that of God within, and Friends’ education is centered in truth, practical learning, scientific inquiry, simplicity, and concern for civic society.

Quakers have a long history of questioning power and engaging in social action for human rights and peace. Today, many Quaker schools or Quaker affiliated institutions of higher education frame their learning environments with social or civic responsibilities and define community expectations through the lens of Friends’ values while still honoring the individual.

As the United States grew from colony to nation, the Quakers advocated for and delivered universal pubic education in Pennsylvania, built colleges, and created private Quaker secondary and elementary schools. The motto of the William Penn Charter School; “Good Instruction is Better than Riches” dates back to its founding in 1689 and still serves to describe Friends’ fundamental belief that knowledge outperforms wealth over time.

In the United States, Quakers were key to the founding of Haverford College (Pennsylvania), Guilford College (North Carolina,) Earlham College (Indiana), Swarthmore College (Pennsylvania), Johns Hopkins University (Maryland), Cornell University (New York), and the Wharton School of University of Pennsylvania (Pennsylvania). All that does not mean that Quakers were perfect. As we see in the stories below, the were human and also strongly influenced by their own time and place.

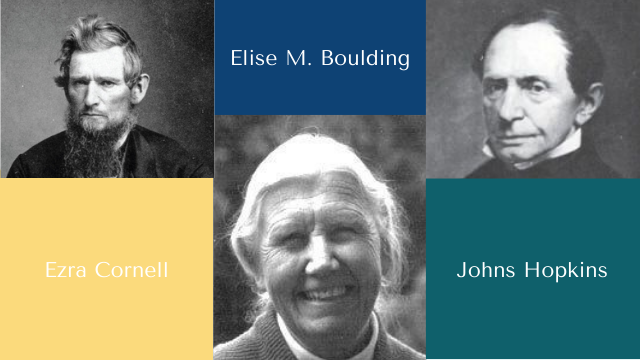

Here follow the stories of three Quakers who had impact as educators and founders.

Elise M. Boulding (1920 –2010) was a Norwegian-born sociologist, author, peace and women’s rights activist. She taught at the University of Colorado and Dartmouth and authored numerous books, including:

- The Underside of History: A View of Women through Time (1976);

- Children’s Rights and the Wheel of Life (1979);

- Building a Global Civic Culture: Education for an Interdependent World (1988); and

- Cultures of Peace: The Hidden Side of History (2000).

Boulding’s life spoke to the integration of peace research, education, and action. She built peace studies programs at the University of Colorado, Boulder, and Dartmouth College. A co-recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1947, she was nominated for a second Nobel by the American Friends Service Committee in 1990.

Boulding and her husband, Kenneth Boulding, raised five children, and she credited her role as a parent with informing her work as a sociologist.

References:

https://montgomery.dartmouth.edu/elise-boulding

https://centerforneweconomics.org/people/elise-m-boulding

Ezra Cornell, (1807-1874) was an American businessman, politician, and philanthropist. He was born in a Quaker family in Westchester Landing, New York, and grew up to become a co-founder of Western Union and co-founder of Cornell University. He was disowned as a Friend for marrying Mary Ann Wood, a Methodist, and therefore considered as ‘outside’ of the faith.

Ezra Cornell was said to be a man of few words who was rarely tactful. He was also a prolific letter writer and a natural mechanic; Cornell faced adversity after the Panic of 1837 when he lost his job as a mill manager for Beebe mills in Ithaca, NY. He was then just 25 years old and already married. Cornell bounced back by taking up the patented plow business, walking between the two geographic territories he had responsibility for (Maine and Georgia) to save money. The work with plows led him to a contract to bury telegraph wires, but that encountered difficulties, as the wires became damp, suffered poor conductivity, and degraded underground. His innovative solution, placing all telegraph wires above the ground, and insulating them with glass as they connected to supporting poles, was developed in partnership with Samuel B. Morse and led to the market domination of Western Union’s telegraph services. Ezra Cornell hired his sister, Phoebe, as his very first telegraph operator.

Cornell envisioned public prosperity and universal fairness for America. He funded the construction of a great public library in Ithaca and built and stocked a model farm, which became a center for the study of agriculture. He served as the president of the State Agricultural Society and a member of the New York State Legislature in the 1860s.

Cornell died in 1874. He was survived by his wife, Mary Anne Wood Cornell, and a son, Alonzo B. Cornell, later governor of New York.

References:

https://rmc.library.cornell.edu/ezra/exhibition/earlyyears/index.html

https://ithacavoice.com/2015/04/ezra-cornell-imperfect-gentleman-whose-university-changed-world/

Johns Hopkins (1795-1873) was an American entrepreneur and philanthropist, born into a Quaker Tobacco farming family. Reports that are now being questioned said that the family emancipated all enslaved persons on their Virginia acreage in 1807, but this does not appear to be true. These now debunked stories say that emancipation reduced the family’s means and capacity, and necessitated withdrawing Johns from school.

The story is interesting in that there Hopkins papers or documents are largely absent, and the stories that were told came from family members who had an interest in sanitizing stories about prominent forbearers. However a careful research of public records by Johns Hopkins University uncovered two critical facts; the Hopkins household housed one enslaved person in 1840 and four in 1850.

All these persons are without recorded names.

Other records show that Hopkins’ grandfather freed eight or nine people, but kept others.

Johns Hopkins University has issued a December 9th report on the research. The New York Times and other newspapers noted that many Hopkins “facts” had been published by a fond and admiring great niece of the University’s founder. All of these are now being re-evaluated.

As very few personal papers exist on the College’s founder, the research is necessarily focused elsewhere.

The New York Times published a December 10th, 2020 story which details the University’s process in researching what is–and is not–true about their founder.

Most people agree that at the age of 12, Johns went to work in the family’s tobacco fields, serving his family as a farmer for five years. The Encyclopedia Britannica says that Hopkins’ “awareness of his own educational limitations and of the needs of the newly freed Blacks would stay with him and influence him for the rest of his life.” And certainly Hopkins showed a care for people of color, even while adhering to segregationist instints in his program design.

But back to young Johns. Noticing that Johns had a mind for trade and finance, his family arranged for him to work for a Quaker cousin in Baltimore at 17. Within three years, he’d become extremely successful in the cousin’s grocery business. He also fell in love with his 16-year-old first cousin, Elizabeth Hopkins, whom he never married due to a Quaker prohibition on marriage between first cousins. The two of them made a pact never marry another (which feels sad), and Johns supported his cousin for her lifetime (which feels compassionate), even building her a home and leaving her a generous legacy.

As Johns created wealth within the grocery business, he was not averse to taking payment in whiskey when store owners lacked cash for payment. He then sold the whiskey under the Hopkins brand name, earning him criticism from other Quakers.

As his wealth accrued, he used it to support others and was known to provide generous, low-interest loans to business-owners who applied for credit. These very low rates of interest undercut other bankers’ businesses (also generating complaints), but he continued the practice, notwithstanding his critics.

Hopkins invested in the wholesale grocery business and prospered mightily. He made investments in real estate, river and steam transportation, and railroads, becoming the largest private individual stockholder in the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. He then retired at the age of 52. In his will, he set up two corporations, one for a hospital and one for a university. He also funded an orphanage for children of color.

Johns Hopkins dedicated much of his life to building businesses and accumulating wealth, which he then gave away.

So how did the fiction around abolition get built? In 1929 a book by a Hopkins great niece lifted up the Hopkins family’s purported engagement in abolition movements. It may be something she believed to be entirely true. No one questioned it. Few looked for supporting facts. Much of the story confused a factual manumission by Hopkins’ grandfather, that ended up being attributed to his father. Here is the first media nugget:

In 1873, at Johns Hopkins’ death, news reports commented on the family’s history of

slaveholding. Of special note was Hopkins’ grandfather – also named Johns Hopkins – who was

said to have manumitted enslaved people in the 18th century. Typical was a Baltimore Sun

obituary which described Hopkins’ grandfather with having run his “landed estate” with “the aid

of some hundred negroes, whom he afterward emancipated.” There was no mention in the Sun

article of Hopkins’ father, Samuel Hopkins, having owned or manumitted enslaved people.

Here is the second nugget:

In 1929, Helen Hopkins Thom, a grandniece to Johns Hopkins, … credited Samuel Hopkins

rather than Johns Hopkins the elder with having manumitted enslaved people, in her book Johns

Hopkins: A Silhouette, published by the JHU Press. Thom reconstructed Hopkins’ life from

family tales, especially those of her late father, and she wrote from the perspective of an

admiring descendant who generally depicted slavery as a benign institution and enslaved people

as contented and loyal. Thom tells of Hopkins’ father Samuel having manumitted his slaves in

1807, in deference to the tenets of the Quaker faith.9 Thom referenced no sources beyond first

and secondhand recollections.

Research this year told a different story. Martha Jones, a John Hopkins Professor, documented the fact that nameless individuals were in fact listed as enslaved persons in the Hopkins Household on public census lists. The University published a December 9th web story on the issue. Excerpts follow:

Over the past several months, JHU history professor Martha Jones, one of the nation’s leading scholars of slavery, abolition, and how Black Americans have shaped the story of democracy in the U.S.; and Allison Seyler, program manager of Hopkins Retrospective, have worked to confirm the connections between newly discovered documents and the Hopkins family, examining census records, city directories, period newspapers, and other public records. The records clearly show that enslaved people were among the individuals laboring in Johns Hopkins’ home in 1840 and 1850, and perhaps earlier. There are no enslaved persons listed in Johns Hopkins’ household in the 1860 census.

The account then goes a little deeper into the story. Here’s how Professor Martha Jones sees it:

“In many ways, there’s little that is remarkable, in the context of the awful history of slavery in the United States, that a man of Johns Hopkins’ wealth and status was a slaveholder,” said Jones, Society of Black Alumni Presidential Professor and Professor of History and the SNF Agora Institute. “While that doesn’t surprise me, the discovery does leave me with as many questions as answers, because we know too little about, in particular, the enslaved people in Hopkins’ household—who they were, what their lives were like, where and how they made their way after they were no longer enslaved. And I remain unsettled that we may not be able to know as much about them as we should want to know, and need to know, in order to tell the whole story.”

In the end, Hopkins contracted and died of pneumonia in 1873. He left $7,000,000 to be divided equally between two corporations (one a hospital, the other a University) set up six years earlier. This sum of money was equivalent to 1/944th of US GNP.

As a result of his bequest, Johns Hopkins University was created in 1876 and Johns Hopkins Hospital in 1889.

Note: This section was updated on December 10, 2020

References:

https://hardhistory.jhu.edu/assets/uploads/sites/8/2020/12/Hard.Histories.12.8.20.pdf

https://hub.jhu.edu/2020/12/09/johns-hopkins-ties-to-slaveholding-reexamined/

https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/about/history/_docs/who_was_johns_hopkins.pdf

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Johns-Hopkins-American-philanthropist

This article is part of a series, and the next part will feature: Nitobe Inazo, Elizabeth Gray Vining, and Joseph Wharton.