“Those who ventured abroad, had handkerchiefs or sponges impregnated with vinegar of camphor at their noses, or smelling-bottles full of the thieves’ vinegar. Others carried pieces of tarred rope in their hands or pockets, or camphor bags tied round their necks… People hastily shifted their course at the sight of a hearse coming towards them. Many never walked on the footpath, but went into the middle of the streets, to avoid being infected in passing by houses wherein people had died. Acquaintances and friends avoided each other in the streets, and only signified their regard by a cold nod. The old custom of shaking hands fell in such general disuse, that many shrunk back with affright at even the offer of a hand. A person with crape [mourning crepe], or any appearance of mourning, was shunned like a viper.” (Mathew Carey, publisher)

Sound familiar, except for the tarred rope and mourning crepe? This was the 1793 yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia, which overwhelmed the city’s residents, Quakers and non-Quakers alike, from August to November. People died, families fled, businesses closed, but volunteers, including Quaker and Blacks, helped the afflicted in basic ways.

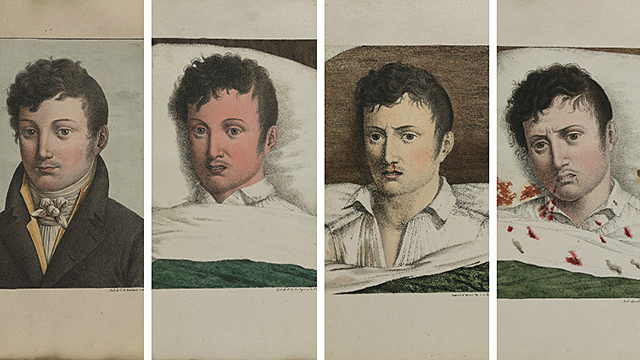

Symptoms of the spreading disease included high fevers, hemorrhages, yellow eyes and skins and black vomit. Benjamin Smith, member of Philadelphia Monthly Meeting, wrote to his father that he had “a great pain” in his head. None understood its real cause—infected mosquitoes, but blamed face-to-face contact, exertion or a moral lapse, such as in theater attendance.

In August, Quaker resident Elizabeth Sandwich Drinker described Philadelphia: “..a fever prevails in the city, particularly in Water Street, between Race and Arch Streets of the malignant kind.. numbers have died of it…” but could be rich or poor, black or white. “Death visits alike the lonely Cottage and the more splendid Dome” (Joshua Cresson, Philadelphia Quaker). It was believed to be more fatal to young men but that Blacks were less likely to get it. Joseph Price: “what is very remarkable the Negros do not take it & are the only people, or nearly so that are implied in burying dead & nursing the sick”.

“One of the carters in the service of the committee reports, that in the performance of his duty he heard the cry of a person in great distress, the neighbours informed him, that the family had been ill some days – and that being afraid of the disease no one had ventured to examine the house; he cheerfully undertook the benevolent task, went up stairs and to his surprise found the father dead, who had been lying on the floor for some days, two children near him also dead, the mother in labour; he tarried with her, she was delivered while he was there, and in a short time both she and her infant expired! He came to the City Hall, took coffins and buried them all.” (Caleb Lownes, Quaker secretary of the Committee)

The first victims seemed to live or work near the Delaware River port so speculation about the epidemic’s causes focused on that connection. “…some say it was occasioned by damaged coffee, and fish, which was stored at Wm. Smith, others say it was imported in a Vessel from Cape-Francois which lay at our warfe, or at the warfe back of our store.” In this statement, Drinker was referring to the revolt in Haiti which had sent many refugees to Philadelphia, so many saw them as the source (the mosquitoes, which were the actual source, probably came on the same ships). Others, including Dr. Benjamin Rush, were convinced that the disease was the result of putrid air from filthy docks, cellars, sewers and privies. But Joseph Price, caretaker of Merion Meeting, may have described the medical response more accurately: “the Doctors Confus’d weighting & prescribing Different treatment, puzzles all their Nateralism for they dye away…”! **Of course, the disease-causing mosquitoes were most prevalent along the docks along the Delaware River.

**There was no cure for yellow fever, but in 1793 well-known Dr. Benjamin Rush was convinced that bleeding was the most likely cure.**

Observers of the disease noted the desolation of the city. For at least three months that year, Philadelphia was quiet (except for the funeral bells) and empty. Isaac Heston wrote to his brother: “You cannot immagin the situation of this city. How deplorable. It Continues to be more and more depopulated, both by the removal of its Inhabitants into the Country, and by the destructive Fever which now prevails.” (He died and was buried at Arch Street before it was over). Joseph Price, caretaker of Merion Meeting, put it this way: “they are flying out of town in all directions, a Stagnation of all kind of business never did the people of that City Exspearance Such an alarm.” Several Quaker observers noted the reduced attendance at Meetings-for-Worship and one noted that the Monthly Meeting for Business at his Philadelphia meeting was the smallest ever, and yet Benjamin Smith noted that participation in Yearly Meeting at Arch Street Meeting in September, 1793 was larger than expected (about 100 attended). John Todd, first husband of Dolley Madison, attended, contracted the disease and died (his wife later married James Madison).

Of course, the high rate of death was shocking to everyone. Historian Mathew Carey calculated at the time that 4041 people died, the largest numbers reached in October, 1793 (more recent estimates range from 5000 to 7500). At the time, Price referred to “a great Mortality in Cyty” and he was shocked that burials were running 100 or even 150 in one day. Besides Todd, Benjamin Smith succumbed, along with Joshua Cresson, Isaac Heston and the last treasurer of colonial Pennsylvania, Merion member Owen Jones, Sr. In the Merion Meeting Burial Ground record, about 20 deaths from late 1793 were probably due to the yellow fever epidemic. That fall, caretaker Price was frantically making coffins for adults and children, including six members of the Erwine family.

Quakers and others were dismayed at the callous attitude of many toward the suffering. Sick people were abandoned by caregivers. Isaac Heston wrote to his brother about Dr. Morris’ widow, going to her own father’s house after her husband died and being turned away. He reported also that one of the bank clerks, who contracted the disease, could find no one to care for him. When Quaker Joseph Inskeep came down with the disease, he asked for help from a family he had assisted but was turned down. He died.

Finally, the mayor of Philadelphia called together some prominent citizens to provide aid to the victims, and so the “Committee to attend to and alleviate the suffering of the afflicted with the malignant fever prevalent in the city and vicinity” was founded. In this group were at least three Quakers: Samuel Wetherill, Thomas Wistar and Joseph Inskeep. They established a hospital outside the city, at Bush Hill, and worked to alleviate the suffering of the sick:

“one of the carters in the service of the committee Reports, that in the performance of his duty he heard the cry of a person in great distress, the neighbours informed him, that the family had been ill some days – and that being afraid of the disease no one had ventured to examine the house; he cheerfully undertook the benevolent task, went up stairs and to his surprise found the father dead, who had been lying on the floor for some days, two children near him also dead, the mother in labour; he tarried with her, she was delivered while he was there, and in a short time both she and her infant expired! He came to the City Hall, took coffins and buried them all.” (Caleb Lownes)

Religious people often look for lessons in afflictions and Quakers did this also. Joshua Cresson asked for forgiveness of the sins of “this People”. In his diary, he asserted his faith that God would not let them suffer more than they could bear and prayed that he could “quicken my pace toward perfection”. Isaac Heston was distressed by living “in the midst of Death”, seeing the bodies carried out and the hearses going by, but hoped that serious reflection would be a “healing balm to the human and Tender heart.

Not until 1881 was the actual cause of yellow fever discovered and not until fifty years after that that a vaccine was developed. But the battle led to Philadelphia having the first city health department and the first urban water system. Because of the role Black citizens played in caring for the sick and dying, It also led to improved relations between whites and blacks, including white support for the first black churches—Mother Bethel AME and AE Church of St. Thomas.

Widespread disease seems to bring out the best and the worst in people. Despite periods of exclusion in their history, Quakers experienced the terror of yellow fever much as many other Philadelphians: as victims, fugitives, caregivers and problem-solvers.

Sources:

- Drinker, Elizabeth Sandwith. Diary of Elizabeth Sandwith Drinker, August 1793, ed. Elaine Forman Crane, in The Diary of Elizabeth Sandwith Drinker, vol. 1. Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press, 1991.

- Foster, Kenneth R., Mary F. Jenkins, and Anna Coxe Toogood. “The Philadelphia Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1793.” Scientific American 279, no. 2 (1998): 88–93. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26070603.

- Heston, Isaac. “Letter from a Yellow Fever Victim, September 19, 1793.” https://journals.psu.edu/pmhb/article/download/41767/41488

- Kashatus, William. “Plagued! Philadelphia’s Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1793. Pennsylvania Heritage, Spring 1993. http://paheritage.wpengine.com/article/plagued-philadelphias-yellow-fever-epidemic-1793/

- Merion Meeting Burial Records. Lower Merion Historical Society.https://www.lowermerionhistory.org/burial/merion/

- Price, Joseph. “Diary”. Lower Merion Historical Society. https://lowermerionhistory.org/?page_id=143029

- Rush, Benjamin. Observations upon the origin of the malignant bilious, or yellow fever in Philadelphia, and upon the means of preventing it :addressed to the citizens of Philadelphia. Philadelphia: : Printed by Budd and Bartram, for Thomas Dobson, at the stone house, no 41, South Second Street., 1799.

- Smith, Benjamin.”Letters to Father Daniel Smith During the Prevalence of the Late Malignant Fever in Philadelphia”, 1793.

- Tighe, Janet A. “Negotiating the Health of the Public: Yellow Fever in 1793 Philadelphia.” OAH Magazine of History 19, no. 5 (2005): 30–35. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2516197