February is Black History Month and there are Quakers of color who have delivered much to our modern world through their faith and advocacy. Knowing the past opens a door to the future that is framed within diversity and inclusivity. Our understanding of America’s history is deepened by the contributions of African Americans who struggled for freedom and equality.

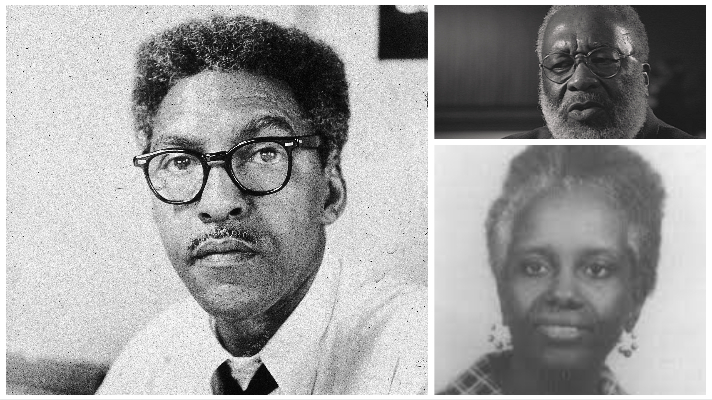

Here are three African Americans who were crucial to our shared Quaker history. Learn how they made an impact on our society:

Bayard Rustin (1912-1987) was a West Chester native who became an internationally known human rights activist. He was jailed as a conscientious objector and worked throughout his life to address the economic, social, and political issues that hurt people on the margins around the world. Rustin protested segregation in the USA, was active in America’s civil rights movement (advising Dr. Martin Luther King on peaceful resistance), and later, in the 1980s, shifted his focus to working for gay rights.

Both morally and practically, segregation is to me a basic injustice. Since I believe it to be so, I must attempt to remove it. There are three ways in which one can deal with an injustice. (a) One can accept it without protest. (b) On can seek to avoid it. (c) One can resist the injustice non-violently. To accept it is to perpetuate it.

— Bayard Rustin

Vera Mae Green (1928-1982), was a pioneer in the international human rights and Caribbean anthropology. She was the first president of the Association of Black Anthropologists (1977-1979), served as Director of the Mid-Atlantic Council for Latin American Studies, and was active in the Society for Applied Anthropology. In 1972-3, she did a study on “Blacks and Quakerism” for Friends General Conference. She was an essential contributor to a 1979 session of Quaker sociologists on problems of peace in the Middle East. A strong advocate for diversity in anthropology, she actively encouraged African Americans and other people of color to pursue careers in the field.

International human rights is an issue basic to the quality of future life and deserving of extensive exploration. The effectiveness of this exploration may be increased by the use of an integrated, multifaceted format which is not only cross-cultural and/or cross-national but also interdisciplinary. Such an approach can reduce the tendency to treat human rights issues in an oversimplified manner.

— Nelson; Green, Jack; Vera Mae (1980). International Human Rights: Contemporary Issues. Stanforville, NY: Human Rights Publishing Group.

Vincent Harding (1931-2014), was a theologian, historian, and nonviolent activist. Even though he was not a Quaker, he was a friend of the community and affiliated with the Pendle Hill Quaker Retreat Center. Harding and his late wife, Rosemarie Freeney Harding, worked as negotiators in the Southern Freedom Movement in the ’60s and were friends and co-workers with such leaders as Martin Luther King Jr., Ella Baker, Fannie Lou Hamer. (Harding provided the initial draft for King’s “Beyond Vietnam” speech at Riverside Church in New York City.) Harding was one of the organizers and the first director of the Institute of the Black World, founded in Atlanta in 1969. After holding several research positions and visiting professorships (including two years on the staff of Pendle Hill), he served as professor of religion and social transformation at the Iliff School of Theology in Denver for nearly a quarter of a century and served as professor emeritus and trustee at Iliff.

You can’t start a movement, but you can prepare for one.

This month is a celebration of people’s journeys as they profoundly impacted society.

There are many resources that tell the story of African American Quakers. Here are two:

Fit For Freedom, Not for Friendship, by Donna McDaniel and Vanessa Julye

Black Fire (edited by Harold Weaver, Jr. Paul Kriese, and Stephen Angell with Anne Steere Nash)