Last summer Philadelphia Yearly Meeting received a significant bequest to PYM as well as a Legacy Fund gift. When the bequest arrived, accompanied by a letter from Pat McBee, the executor, we knew that Amy Kurkjian had an interesting life story. There was a second story, too. Amy’s executor and care advocate, Pat McBee, was challenged to figured out how to support Amy’s goal of living independently. Pat found a way forward and the causes near and dear to Amy’s heart, including PYM, benefited. So did Amy!

A Life Framed by Quaker Purpose

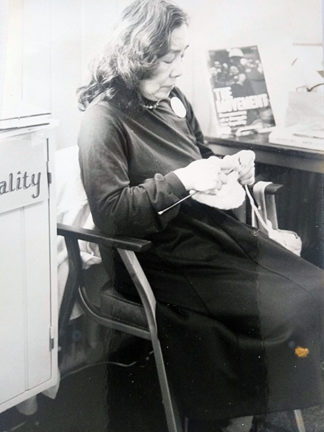

Perhaps you remember a Friend—with knitting needles and balls of yarn—at almost every Yearly Meeting Sessions gathering encouraging others to knit or crochet squares during business sessions. That Friend was Amy Kawabe Kurkjian who later helped to assemble the squares into colorful quilts. Industrious, creative, charitable, and practical, Amy was a longtime volunteer at Philadelphia Yearly Meeting and a faithful participant in the life of the Meeting. The Friendly Crafters project was just one of many initiatives she touched.

Perhaps you remember a Friend—with knitting needles and balls of yarn—at almost every Yearly Meeting Sessions gathering encouraging others to knit or crochet squares during business sessions. That Friend was Amy Kawabe Kurkjian who later helped to assemble the squares into colorful quilts. Industrious, creative, charitable, and practical, Amy was a longtime volunteer at Philadelphia Yearly Meeting and a faithful participant in the life of the Meeting. The Friendly Crafters project was just one of many initiatives she touched.

Self-possessed, and efficient, Amy would arrive on her scheduled volunteer days at PYM to help the business office maintain files. PYM accountant, Celeste Richardson can still see her, petite and well-organized, filing papers. She even recalls Amy’s favorite chair – a brown oak library chair we still have (and use) in the Friends Center Office.

Amy was a Japanese American who moved to the East Coast following World War II. Both parents were originally Japanese and had emigrated to Hawaii. Amy was born in South Hilo township, in the Village of Honomi in 1923. The name on the birth certificate was Amy Kawabe. There were five siblings in the family, two boys and three girls. Amy was sandwiched in the middle, between two sisters.

From South Hilo, Hawaii, the Kawabe family moved to California for better schools. As part of the internment of Japanese heritage U.S. citizens, Amy’s family was forcibly displaced in WWII. They took the option of deploying as farm workers in Utah rather than being sent to an internment camp. Meanwhile, both of Amy’s brothers enlisted in the U.S. Military during World War II and both died during the war. The war also brought Amy into relationship with her future husband, an Armenian American, Ernie Kurkjian who did his Civilian Public Service with the displaced Japanese Americans.

Intersecting Trajectories; Pat, Amy, and Ernie as Philadelphia Quakers at Central Philadelphia Monthly Meeting

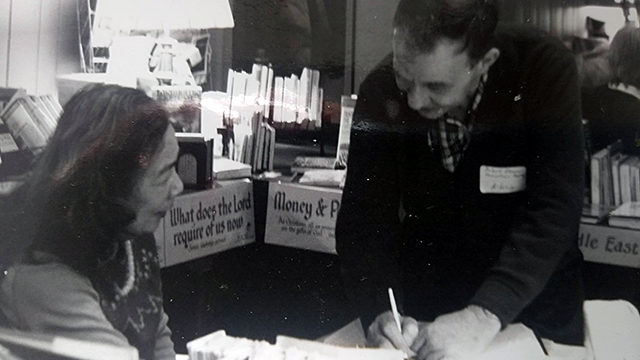

Pat McBee recalls first attending Central Philadelphia Monthly Meeting (CPMM) in 1970, and joining a year later. At the time, Amy’s husband, Ernie, was still alive, and Ernie was among the first people to greet Pat. Pat was working for Friends General Conference in what was then called the ‘Quaker Quadrangle.’ Friends Center wasn’t yet built, and Ernie was the director/manager of the Friends Bookstore, located in a Yearly Meeting-owned building at the corner of Third and Arch street. Later the bookstore moved up to Friends Center.

On Feb 12, 1971, Ernie died suddenly at 56 years old. He was still working for the bookstore at the time of his death. Amy was just 48. A widow, she completed college at Temple, then went back to California to undertake a master’s degree in holistic health and to be with her parents in their last years. After completing her degree, she returned to Philadelphia and reconnected with the Philadelphia Quaker community. Back then, Pat says, PYM Sessions were like family reunions—places of connection.

As time ticked on, the house the Kurkjian’s owned on Spring Street in the Logan Square neighborhood proved to be a good investment, quietly appreciating each year. When they first arrived, the neighborhood was run-down, today it’s a highly desired address within easy walking distance of the Franklin Institute.

It is the house that made the legacy possible.

Pat’s Reflections: Meetings as Support Communities

As Pat puts it, “part of this story is that Amy and I were friendly acquaintances but … we didn’t know each other well until about 10 or 12 years before she died. This was after she’d outlived her designated first power of attorney, who was PYM’s staff person for the committee on aging. By that time Amy was volunteering for the Yearly Meeting.

“My guess has always been, but I never asked her, that Amy looked around the room when she needed a new power of attorney and thought, ‘Pat McBee is a responsible person, I’ll ask her.’

“There are background ways that meeting (members/attenders) look after each other. It’s not … an official Care and Council activity to say; ‘would somebody please help Amy put her final affairs in order?’ It’s more like one member of a meeting asks another one to do a service.

“For a few years there was nothing I needed to do. She was living her life as a very independent person and she kept me—and the meeting—at arms’ length. She had made excellent end of life plans, had her money invested in tax exempt bonds, and was signed up for Friends Life Care.

“As she started declining there came a time when none of us could reach her; she wouldn’t answer the phone. So, I picked up the key she’d left at the meeting and biked over. I rang her next-door neighbor Avi’s doorbell. Avi and I then collaborated on supporting Amy because she was no longer able to care for her home or to adequately provide for her groceries. We contacted Friends Life Care and a caregiver to come in for a few hours a day.”

Amy was then 90. For the next seven years Pat managed her affairs. Amy went from receiving four hours of caregiving each day, then to eight hours, and finally to overnight care.

Pat recalls that at first Amy “paid the bills and I mailed them, then she advised me, and I wrote the checks, then we reached a stage where I paid her bills. All along I did things on her behalf – trying always to do things that she would choose.

“However, twice I was utterly daunted by decisions she may not have chosen. Amy wanted very much to be in her own home, but needed repairs to the house were soaking up money, the cost of 24-hour care was heavy, and I was fearful she would run out of funds. So, I consulted with her lawyer and the case manager with Friends Life Care about how to turn the house into money that could support her. It became clear that the best thing to do was to sell the house. We moved her out temporarily so that repair work could be done. After a month she agreed that she would never move back, and we brought her to Chandler Hall around the corner from where I was then living.

“Her health became increasingly frail, and after a few years Chandler Hall contacted me about moving her to hospice. Making the decision to move her out of her home and making the decision to deny curative medical care – that’s more responsibility than I’d wanted for someone else’s life.

“But then Amy gave me a blessing about putting her on hospice the Monday after her 97th birthday.

“Pat had visited and thrown a little birthday party for Amy. “I said ‘Amy, do you know how old you are?’ And she said ‘No, how old am I?’ And I said ‘97’ To which she said, “that’s too old!’ So, I took that as an opportunity, and I asked her, ‘Amy do you ever think about the end of your life? And she said, ‘I think about it all the time, I’m tired, I want to go home.’”

Pat said that hospice turned out to be a complete plus for Amy. She did not require any special medical care and she was regularly visited by nurses and a chaplain during the COVID-19 lock-down. Overall, it added to her quality of life. A few weeks later she slipped away quietly in her sleep.

The House and the Legacy

“Amy was a staunchly independent person…Central Philadelphia Meeting and the Yearly Meeting I think were her family. When Amy retired, hanging out at the Yearly Meeting office was something for her to get out of bed for. I’d be riding my bike to work, and I would see her … (walking) … down the Parkway, (heading from her house toward PYM).”

For Amy, Pat says, Quakerism threaded “through (everything). It was Ernie’s Civilian Public Service (as a conscientious objector) that caused them to meet.”

In the end, the three-story row house Amy and Ernie lived in was sold, torn down, and turned into a four-story building with several residential units. That sale supported other dreams of Amy’s – to leave legacies that made a difference.

Amy’s generosity ended up being twice directed towards PYM. First, when she set up a Charitable Gift Annuity (CGA) that she outlived, and again when her estate was settled in 2021.

With the bequest, PYM received an amount similar to what would have come from the CGA had Amy lived according to a more typical life expectancy.

Amy’s PYM bequest has supported Membership development grants, the Legacy Fund, and unrestricted endowment growth. But there was more. In addition to providing for PYM, Amy’s estate supported family members, Green Street and Central Philadelphia Meetings, and three different non-profits that deal with hunger. One that is local, another that is national, and a third that is an international organization. It also supported a senior center in South Philadelphia that Amy relied on.

Pat McBee notes that “Amy was devoted to the Yearly Meeting! She was there on a regular basis during her retirement doing clerical work. She ran the project where you pick up a pair of knitting needles, and some yarn and make a square for a quilt to keep your hands busy during Yearly Meeting, and then I believe she helped assemble the quilts (to be given away).”

Celeste Richardson, PYM accountant recalls, “She would come in two or three times a week and file papers for us, support the Mary Jeanes Loans documentation, and help us in accounting.”

In spirit, with this legacy, and this story, Amy’s love of faith lives on as inspiration to others.