Benjamin Banneker (1731-1806) was a self-educated African American mathematician, astronomer, surveyor, compiler of almanacs, and writer. He was also a regular attender at Quaker meetings and an abolitionist who gained fame and recognition for his contributions to science and his prescient correspondence on multiple subjects, including race, with key intellectuals of the time.

Banneker was born to a freeborn African American mother, Mary Banneky, and a West African father, Robert, who had bought his freedom from enslavement. He was raised in Baltimore County, Maryland, on a 100-acre tobacco farm. His grandmother, an Irish-born former indentured servant, taught him how to read and write, and Benjamin continued his studies for a time alongside white and black classmates at a small Quaker school. As a result of his proficiency in arithmetic, Banneker’s story is uncommon and varies from other people of the same period.

As the oldest of four children, Banneker took over the farm when his father passed away in 1759, but he continued to educate himself and garnered local attention and fame by building a clock out of wood that kept perfect time.

When a family of Quaker brothers, the Ellicotts, moved close to Banneker’s farm to build their mill, the two neighbors formed a friendship that introduced Benjamin to astronomy. One of the brothers, George Ellicott, was an amateur astronomer and lent Benjamin the necessary books and telescope to acquire proficiency in the science of astronomy. Banneker went on to accurately calculate the positions of the sun and moon.

Tyson Ellicott’s “A Sketch of the Life of Benjamin Banneker, from notes taken in 1836,” describes his relationship with the Quakers:

“His genius, and the nature of his contemplations, rendered him in a great measure, superior to such perplexities; and the pacific principles which he admired, taught him forbearance, and the forgiveness of injuries. Although he made no pro-fession of religion, he loved the doctrines and mode of wor-ship of the Society of Friends, and was frequently at their meetings. We have seen Banneker in Elkridge Meeting house, where he always sat on the form nearest the door, his head uncovered. His ample forehead, white hair, and rever-ent deportment, gave him a very venerable appearance, as he leaned on the long staff (which he always carried with him) in quiet contemplation.”

Banneker’s mathematical expertise and scientific knowledge were admired by many, and he was invited to assist one of the Ellicott brothers with an initial survey of Washington, D.C. An abolitionist, Banneker also published abolitionist material south of the Mason-Dixon Line. His accomplishments led to correspondence with prominent political figures like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson.

A letter from Benjamin Banneker to Thomas Jefferson. August 19, 1791. (Founders Online, National Archives) contains a paragraph that exhorts Jefferson to take a more public role in addressing race and human capacity:

“I apprehend you will embrace every opportunity, to eradicate that train of absurd and false ideas and opinions, which so generally prevails with respect to us [African Americans]; and that your sentiments are concurrent with mine, which are, that one universal Father hath given being to us all; and that he hath not only made us all of one flesh, but that he hath also, without partiality, afforded us all the same sensations and endowed us all with the same faculties…” – Benjamin Banneker

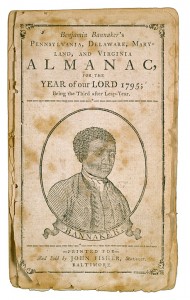

Apart from Banneker’s work on the survey of Washington, DC, he spent personal time assembling and printing an almanac for Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia which included medical information and treatment options as well as lists of tides, astronomical data, and eclipses. He sent his first almanac to Thomas Jefferson in a bit to convince him, and others, to rid themselves of beliefs in white racial superiority.

In response, Jefferson wrote a letter that informed Banneker that he had sent the almanac to the Academy of Sciences in Paris and applauded his accomplishment:

“…no body [sic] wishes more sincerely than I do to see such proofs as you exhibit, that nature has given to our black brethren, talents equal to those of the other colours of men, and that the appearance of a want of them is owing merely to the degraded condition of their existence both in Africa & America…” – Thomas Jefferson

Banneker possessed a philosophical disposition and was always curious to gain knowledge. He never married and died on the farm at the age of 75 in 1806 after a long-term illness. Banneker’s log cabin home, and the famous wooden clock, were both lost to posterity in a fire on the day of his funeral.