South Main Street, Quakertown, PA, doesn’t look like a heart-stopper today as cars whiz by. But back in September 1851, as William Parker (an African American farmer from Lancaster, PA) escaped north to Canada after taking part in the Christiana Riot, it must have felt like one. As he moved from safe house to safe house on the underground railroad, each stop was only a little bit farther on the long road north to Canada. He must have always been worrying about being captured.

But William Parker made it to safety, thanks to interventions by Quakertown Friends Richard and Sarah Moore and their cohort of station masters on the underground railroad. The Moores ended up helping more than 600 fugitives escape from slavery.

This is now commemorated by an historic marker, unveiled on Saturday, September 14th. Placed just outside the Moore’s tidy stone farmhouse (now privately owned residences) at 401 South Main Street, Quakertown, PA, the marker has been more than 15 years in planning. Quakertown Alive first applied for the marker in 2004, but was rejected. In 2014 a local Quaker at Richland Meeting, Jack Schick, took up the cause, reapplying with additional information from Quaker archives; he received provisional approval. Finally, in 2018, a third application by the Quakertown Historical Society–with documentation from the Richland Library company and research from another Quaker, Kim Landon–received approval.

The story of how the Christiana riot intersects with Quakertown’s Richland Meeting and its connection to the underground railroad follows.

Lancaster farmers, William Parker and his wife Eliza, had been sheltering four men who’d escaped enslavement by Maryland farmer Edmund Gorsuch. Harboring fugitives from the the South was a common activity in the Parker home; William and Eliza had both escaped slavery and now worked to ensure others succeeded as well. It was a risky activity, as William noted in later interviews: “Kidnapping was so common…that we were kept in constant fear….We would hear of slaveholders or kidnappers every two or three weeks: sometimes a party of white men would break into a house and take a man away…and again a whole family would be carried off….So completely roused were my feelings that I vowed to let no slaveholder take back a fugitive if I could get my eye on him.”

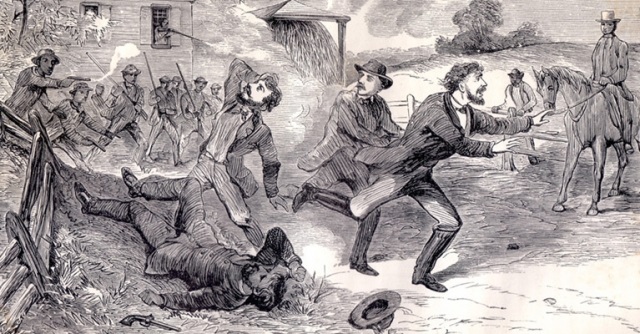

Maryland farmer, Edward Gorsuch considered himself an enlightened slave owner; he believed he treated the enslaved well. He was offended that any of his men would escape, and when Noah Buley, Nelson Ford, George Hammond, and Joshua Hammond ran away, Edward wanted to recapture them. Tipped off that they were living at Parker’s Lancaster farm, he secured arrest warrants from Philadelphia and embarked to Lancaster by train. He arrived at the Parker’s farm with US Marshals, in an attempt to recapture the men during a dawn raid. A struggle ensued and Eliza summoned help by blowing a horn. A large group of free and formerly enslaved African Americans and two white pacifist Quakers showed up. The pacifists would not help the marshals capture the men, and urged the marshals to depart, for in their opinion the men had the right to defend themselves from enslavement. In the struggle, Edward Gorsuch was killed and and his son was wounded.

William Parker was a wanted man and had to flee. Eliza stayed put, was arrested and brought to trial.

Thirty-seven participants were tried, including the two white Quakers, Elijah Lewis and Castner Hanway. Hanway was the first to stand in court. In a surprise win, he was found not guilty, as were all 36 others. This was considered a victory for the abolition movement, but still cost the Parkers their settled life in Lancaster. After the trial, Eliza left home to join William in Canada. Their story was published in the Atlantic Monthly, according to local historian, Dr. Robert Leight.

The route William Parker took was a well-traveled path stewarded by a network of like-minded individuals. They were aware that while they risked arrest or fines, those fleeing slavery risked recapture and enslavement, punishment, trauma and death. Richard Moore and his wife Sarah Foulke worked closely with a network of other Quakers, former slaves, and local abolitionists to hide the freedom seekers on their route north.

Historian Dr. Robert Leight writes that “Richard Moore’s home and pottery became known as the northernmost ‘station’ in the Underground Railroad in Bucks County. The escaped slaves, or ‘passengers’ would come at night from other ‘stations’ from either Chester County by way of Norristown or from lower Bucks County. When it was safe they would be moved either to a Quaker meeting in Stroudsburg or to Easton for their journey northward.”

Most went on foot or sometimes in carts as they traveled towards freedom and new lives, but some stayed put, like carriage driver Henry Franklin (enslaved as Bill Budd), integrating the Quakertown community. Edward Maygill, a Swarthmore college professor in the early 1900s, published this description of fugitives arriving at Quakertown in The Intelligencer in 1907. “Many of the fugitives, on reaching Quakertown, feeling comparatively safe, were willing to hire out there, and Richard Moore was ever willing to give them work himself, or find them employment among his friends and neighbors. Still there were many slaves whose fear was so great that they were anxious to be passed on as soon as possible to a real land of freedom in Canada. These were, of course, sent on at once, and generally with letters to friends in Montrose or Friendsville. Much of the route between Quakertown and these further stations, up the valley of the Lehigh and the Susquehanna, was through a then unsettled country where the probabilities of discovery and arrest were but slight. But there, as elsewhere, most of their traveling was done at night, they lying safely concealed in some dark ravine or impenetrable morass or brushwood by the day.”

The Saturday, September 14, 2019 unveiling of the commemorative plaque drew about 100 visitors and local residents. They toured Quakertown shops and buildings, the Historical Society, and the Richland Meeting House and grounds. The day culminated with a 1:00 ceremony outside Moore’s stone home. It featured local politicians, the African American Museum of Bucks County (AAMBC) represented by several board members including Linda Salley, President, and William H. Reed, Vice President, and an A Capella version of Lift Every Voice and Sing, the Black National Anthem, sung by the Back Bench Boys.

Ruben Christie, a trustee of AAMBC was present with his 11 year old son, Preston–a student at Maple Point Middle School. He describes AAMBC as a “mobile museum that brings programming into the school systems…through scholarship awards…display of many of the artifacts (owned by AAMBC) and the African American experience itself. We do this by partnering with organizations like the Mercer Museum, Pearl S. Buck House, and the Bucks County Travel Bureau as well as other institutions in Bucks County.” Christie, who has an MBA from University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School and works for SUEZ, a French water management company, said that events like the unveiling are just “phenomenal, because it shows that it was not just African Americans, there were others that really cared about the (anti-slavery) cause and did their best to support abolition, and worked,quite frankly, to annihilate slavery.”

The AAMBC also has programming that gathers people at events and talks that raise awareness of African Americans who’ve contributed to the county in significant ways. Their project, “Bucks County Hidden Figures” has highlighted Leonard Miller, a NASCAR race car owner who broke the color barrier in 1976, and Judge Clyde W. Waite, the first African American Judge in Bucks County and a graduate of Yale Law School.

The work of developing effective programs that help people access previously hidden knowledge is exciting. Ruben Christie concludes; “There are a lot of African Americans who have rich history that we are honing; we call them our Bucks County Hidden Figures, but we want to make them hidden no more.”

Bucks County Quaker meetings interested in learning more about the African American Museum of Bucks County may call 215-752-1909 and visit the website infoaambc.org.

Stay tuned for more about Richland Meeting in a second article.

For resources assembled and curated about African American History visit www.blackpast.org