Are we are beholden to our past, or entirely free of it? It turns out that this all depends on whether you are willing to see history as a teacher. History speaks to what happened to those who walked this land before us. There is a lot to uncover, and wonder about; not all of it bears up so well in the world we live in today. But it is important to know the facts.

Valley Meeting is looking to grow a sense of community around its five acres of land. This comprises a burial ground, a meeting house, a parking lot and sheds, a community garden, a labyrinth site, and a hoped for role as part of a network of neighborhood walking trails on the fringes of that urban jungle, King of Prussia. As a way to launch a sense of storytelling around the meeting, and its history, here follows a brief history of those to whom the meeting has offered a final resting place along with some stories about how they got there.

The Past is Present…you just have to look for it

Valley Meeting Friends’ Burial Ground has a rich and storied history.

It contains the remains of early Quakers, Revolutionary War soldiers, many 19th century African Americans as well as veterans of the Civil War and later American conflicts.

Its story begins with Lewis Walker, one of the first European settlers in Tredyffrin Township, who arrived in 1698. He purchased the land for his farm and built a home, known as Rehobeth, in 1702 on property located behind the Burial Ground. Walker, who was one of many Welsh Quakers who came to the Great Valley and its rich farmland, invited a group of fellow Quakers to worship in his house. It was they who founded the meeting.

Although the graveyard existed by 1719, it was officially bequeathed to the meeting upon Lewis Walker’s death in 1728.

In 1731, a meetinghouse, probably made of logs, was erected fairly close to the road in the northeast section of the present Burial Grounds. The small 1731 building served the Meeting for 150 years, until 1871, when Valley members directed that a new, larger meetinghouse be built across Old Eagle School Road.

War Intrudes on the Community

Before 1775, Welsh Quakers and their neighbors prospered and worshiped in peace. During the American Revolution, however, everything changed. Quakers and other citizens of the Great Valley were greatly impacted by the war as contending armies moved through the area.

The British Army encamped at Tredyffrin in September 1777, and the Continental Army built its encampment at Valley Forge in December 1777, where they stayed until June of 1778. Army foraging stripped the region’s citizens of their crops and livestock as well as their peace of mind.

Since most Friends adhered to the Peace Testimony, they did not participate in war. In many cases this included not paying a fee to support the Pennsylvania state forces. Consequently, Pennsylvania’s Revolutionary War government persecuted those Friends who refused to pay war assessments and did not support the war.

During the first months of the Valley Forge Encampment, the Continental Army took over Valley’s meetinghouse and converted it into a hospital. Rhode Island Quaker General Nathanael Greene kept his headquarters at Rehobeth. While the meeting served as a hospital, those soldiers who died there–as well as the ones who died in camp a short distance away–were buried “outside the western wall” of the meetinghouse.

The approximate location of the soldier’s mass grave site is at the southwest corner of the burial ground, and marked by a monument.

Accounts of the soldiers from Greene’s Virginia/Pennsylvania troops indicate that the causes of death for the men buried here were primarily from diseases like dysentery, typhus, typhoid and the flu. It is unknown how many of the local families also contracted some of these deadly diseases; certainly there were some.

It would be some time before the region would recover from the armies’ depredations.

Who is Resting Where?

The oldest sections of the cemetery contain many unmarked graves.

The oldest sections of the cemetery contain many unmarked graves.

In keeping with the Quaker principle of simplicity, this tradition is still present with modern gravestones that remain small and unadorned.

The Walker family was intimately involved in the burial ground from its beginning and likely responsible for burials from the start.

The earliest records show only the names of the Quakers buried here, but not the placement of graves. Starting in 1800, the Walker family kept somewhat more complete records.[1] The Walker records reveal that at least 70 African Americans were among those buried here in the 19th century.

This represents the largest known and documented pre-Civil War African American burial ground in the Tredyffrin area.[2] Previous relationships between local black residents and the Valley Friends offer some clues as to why the Quakers welcomed these burials of non Friends at a time when this was not a common local practice.

Valley Meeting Resettles Victims of Enslavement

While Quakers became well known for their abolitionist efforts, some of them–like other prominent 18th century Pennsylvanians–owned enslaved persons. Eventually pushed by Quaker activists and changing attitudes in the North, they began to abandon slaveholding and by 1775 declared that no slaveholder could be a formal member of the Society of Friends. Pennsylvania officially abolished slavery in 1780, but the practice did not fully die out for some time.

Former slaves and their children had very few prospects and the Valley Friends felt an obligation to employ, house and tend to their religious education. This care extended beyond their life, allowing them to be buried at the graveyard.

A ship is captured!

From the Philadelphia Inquirer, June 19, 2016:

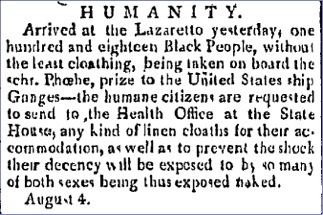

“Arrived at the Lazaretto yesterday, 118 Black People, without the least clothing, being taken on board the schooner Phebe, prize to the United States ship Ganges,” ran a call placed in the Pennsylvania Gazette, referring to the quarantine station in Essington, on the west bank of the Delaware River. “The humane citizens are requested to send to the Health-Office, at the State House, any kind of linen clothes for their accommodation, as well as to prevent the shock their decency will be exposed to by so many of both sexes being thus exposed naked.”

A sympathetic federal judge ruled in favor of the illegally captured Guineans – with each given the legal surname of Ganges – and placed them in the care of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society to work as indentured servants.

The African Americans buried in the cemetery bearing the surname Ganges offer evidence of how slavery was contested in the beginning of the 19th century in a case challenging the institution 39 years before the more famous Amistad incident.[3]

In the summer of 1800 the U. S. Navy sloop Ganges intercepted two American slave schooners. Since this was a violation of the Slave Trade Act, the captive African victims were brought to Philadelphia where their case was to be be decided by the federal authorities.

In the summer of 1800 the U. S. Navy sloop Ganges intercepted two American slave schooners. Since this was a violation of the Slave Trade Act, the captive African victims were brought to Philadelphia where their case was to be be decided by the federal authorities.

Letter to Jared Ingersol, Philadelphia, Pa., from Secretary of the Navy

Mr Calvin Stevens has brought into Delaware, the Schooner Phoebe of Charleston with 120 Negroes, captured by the Ganges Captn Maloney [Lieut. John Mullowny, U. S. Navy]. The act of Congress of the last Session intended to annihilate the Slave Trade, is silent as to the disposition of the slaves, It was expected no doubt, the Captains making the Captures, would sell them in the West Indies. I have directed Mr. Stevens to apply to you for instructions how to proceed.

I suppose measures will be taken by the Government, or by some of the societies for laudable purposes in Pennsylvania to bind out the Blacks for a few years, until they can learn the language of this Country.

From the Gazette of the United States, & daily advertiser

The following incident requires not the aid of the pencil to awaken every feeling congenial to humanity, nor, in exciting our tenderest sympathy for the unhappy sufferers, can’t fail to rouse the keenest indignation against the authors of such inhuman wrongs. Two vessels, belonging to citizens of the United States, concerned in the infamous traffic of human flesh on the coast of Africa, have been lately captured and sent info this port by the Ganges sloop of war.

Taken at different times, they arrived separately at the quarantine station, the one having on board one hundred and eighteen, and the other sixteen unhappy victims. With a view to their health and convenience it was deemed proper to land and encamp these unfortunate people. Scarce had this benevolent measure been effected, and the miserable Africans mingled will1 their fellow sufferers when a Husband and Wife! who had been torn from their home: and happiness, and hurried on board separate vessels by their brutal oppressors met, and recognised each other. Lost, for a moment, in an ecstasy of surprise they exhibited a scene of tenderness, which would have softened the savage hearts of those who had occasioned their separation. But the meeting was more than the unhappy female could support ; -her frame, shaken by the influence of her affections, yielded to the shock, and she was prematurely a mother!

Let the: monsters who encourage and who practice this horrid traffic, reflect on the vengeance of an offended God. An appeal to their conjugal or their parental feelings were a lost hope, and a mockery of humanity. To console the feelings of our readers, we can assure them that the beneficence of the Abolition Society, and the general sympathy of our citizens have greatly alleviated the sufferings of these much injured people; and we are happy in knowing that the unfortunate woman is recovering.

Federal Judge Richard Peters ruled that the captives were to be set free, gave them all the surname Ganges, and arranged through the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, to put them under the care of mostly Quaker Philadelphia area families.

Here follow Abolition Society minutes:

1800 Seventh Month.—A special meeting of the Society was called at the suggestion of the committee on the slave-trade; their minutes were produced, by which it appears that two American vessels, having on board a considerable number of black people, supposed to have been bound to the Havanna, had been captured by one of the armed vessels of the United States, and sent into this port; and that the said black persons are now in circumstances demanding the attention of this Society. A committee was appointed to watch over their situation, and that of any others who may be hereafter brought in under the acts of Congress, against the slave-trade, and to afford them such assistance and protection, by co-operating with the officers of the General and State Governments, as may be necessary, and to provide places for such as are found to be free.

The Ganges Africans (whose ages ranged from children to teens, to 21 year-olds) were indentured to families so that their physical needs could be met while they were taught to read and write English and learn a trade that they could use when free.

Thus through a strange twist of fate, individuals such as Curry Ganges ended up under the protection of members of Valley Friends Meeting. The location of the twelve members of Curry Ganges family buried at Valley Friends is unknown as they occurred before Valley Friends marked graves with stones, and the Walker records rarely indicate a grave location.

For additional research about the Ganges families and the people that took them in, see the March 2018 Ganges Family project by Michael Kearney of Wayne, Pennsylvania.

I have undertaken a project to systematically explore the descendants of the Ganges Africans and, to a lesser extent, the citizens of Pennsylvania who took them in as well as the owners from Newport, Charleston, Sierra Leone, and London who expected to benefit from their kidnapping and sale. This web site is the place where I will present the ongoing results of my research and invite others to participate by sharing their knowledge of the Ganges family.

Michael Kearney, 2018

The Civil and Second World Wars Fill the Earth with Veterans

Another 19th century event that left an imprint on the graveyard was the American Civil War.

As with earlier wars, Friends had to wrestle with the Peace Testimony in deciding whether to serve. In the case of the Civil War, the pull was stronger because the war became one not just to restore the Union, but end slavery in America for good.

The numerous Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) flag markers represent both Valley members who served, and the growing category of non-Quakers buried there, such as the Walkers and Stephenses, all of whom still had strong family ties to the Meeting.

A second large group of flag markers observed in the graveyard are those of the Second World War. Again, although we can’t say with certainty in all cases, the veterans of that era include Quakers who served as well, as non-Quakers who served and chose to continue to use the “family” graveyard.

It is known that some members of Valley chose non-combat service in WWII, but we do not have a comprehensive list. WW II and later graves do contain unit and rank indicators, and one indicates the grave of a medic. One woman whose grave shows a military flag marker served as a nurse.

Further research might reveal why the graves of two other women have military flag markers.

Valley Friends Burial Ground continues to serve the members and descendants of the meeting as an active cemetery. The unmarked graves of the early families, Revolutionary War soldiers and African Americans, as well as veterans and the recently interred all speak of the 300-year-old history of this burial ground and of Quaker values that have been tested over time.

Portions of this article have been previously posted on Valley Meeting’s Website. While Valley Meeting is still closed for in-person worship the community continues to meet virtually. There is more information on their website.

[1] Walker Family Burial Accounts, 1800-1887, Friends Historical Library, Swarthmore College

[2] Patricia Henry, “Early African American Burials in 19th century in Valley Friends Meeting Burial Grounds,” Tredyffrin Eastown Historical Society, Volume 51: 1

[3] https://www.ushistory.org/laz/history/ganges2.htm