In conjunction with its story on Quakers involved in the suffragist movement, Merion Meeting researched the commitment and leadership provided by the African American women’s club.

During the Saturday, October 3rd, virtual event event hosted by Merion Meeting’s History and Archives Committee, a slide show was devoted to the important story of African-American activists’ involvement in securing women’s right to vote.

The presentation was researched and created by Janet Frazer for Merion Friends Meeting with technical aid from Susanna Frazer.

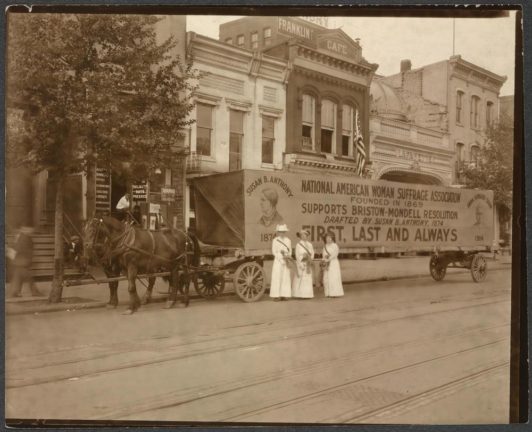

The 1910s were an era of violent racial conflict with riots in southern and midwestern cities; northern whites adjusted uneasily to the massive influx of migrating African-Americans from the South. Although significantly larger percentages of black than white women believed that they deserved the franchise, and although black leaders spoke out for voting rights, the major woman suffrage organizations discouraged the participation of African-American women. At an 1899 meeting, suffragist Lottie Wilson Jackson tried to introduce a motion for NAWSA to condemn segregated public transportation. The motion was tabled.

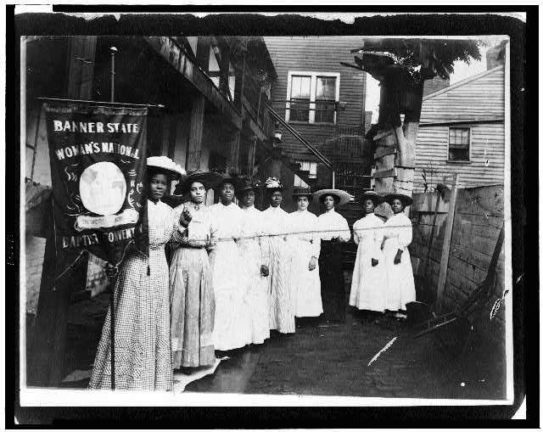

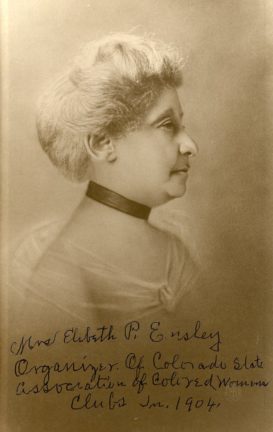

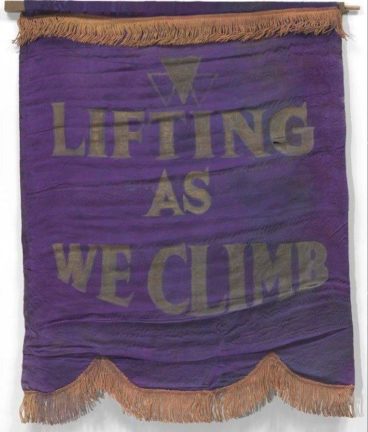

Many African-American women were active in the women’s suffrage movement. Their efforts toward gender equality began in black churches and in black women’s clubs. While some local chapters of the white-dominated NAWSA were more accepting of black participation, others were not. National leaders failed to denounce white supremacy at the 1911 national conference, fearing that might anger some members and male supporters. Sometimes black women worked with white suffragists, sometimes alone.

Mary Talbot, a member of the National Association of Colored Women and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored Peoples, concentrated her efforts on black suffrage: “with us as colored women, this struggle becomes two-fold, first, because we are women and second because we are colored women”(1915).

Frances E.W. Harper joined the new American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), which supported suffrage for both blacks and for women and took a state-by-state approach to securing women’s right to vote. As Harper proclaimed in her closing remarks at the 1873 AWSA convention, “much as white women need the ballot, colored women need it more.

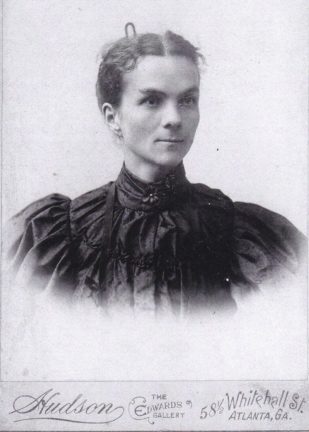

Mary Church Terrell participated in NAWSA meetings and activities, even as the new women’s organization discriminated against blacks to woo southern and white male support for woman suffrage. She also served as president of the National Association of Colored Women.

Mary Church Terrell participated in NAWSA meetings and activities, even as the new women’s organization discriminated against blacks to woo southern and white male support for woman suffrage. She also served as president of the National Association of Colored Women.

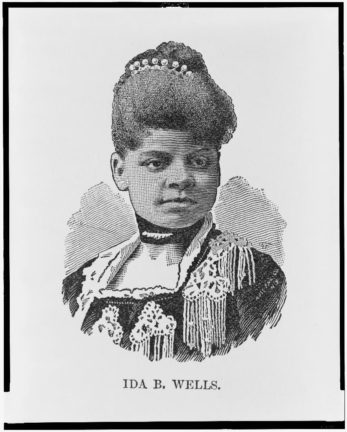

Ida B. Wells, a college-educated journalist, founded the first Colored women’s club in Illinois. At the 1913 March in Washington DC, she refused to march at the back of the parade and joined the Illinois delegation of white women.

Ida B. Wells, a college-educated journalist, founded the first Colored women’s club in Illinois. At the 1913 March in Washington DC, she refused to march at the back of the parade and joined the Illinois delegation of white women.

Hattie Purvis, from a family of Philadelphia reformers, was active in white-dominated Suffrage organizations, including the Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association, and was a delegate to the white-dominated National American Woman Suffrage Association.

Adella Hunt Logan became a professor at Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee Institute. As a member of the white-dominated National American Woman Suffrage Association, she promoted suffrage as a way of stopping violence against women.

Nannie Burroughs was active in the National Association of Colored Women, the National Association of Wage Earners, and the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History.

They advocated for women’s rights as well as to “uplift” and improved the status of African Americans. Unfortunately, racism persisted even in the most socially progressive movements of the era.

Sources

Ansah, AMA. “Votes for Women means Votes for Black Women.” National Women’s History Museum. AUGUST 16, 2018.https://www.womenshistory.org/articles/votes-women-means-votes-black-women. Accessed March 28, 2020.

“Between Two Worlds: Black Women and the Fight for Voting Rights.” National Public Radio. June 10, 2020. https://www.nps.gov/articles/black-women-and-the-fight-for-voting-rights.htm. Accessed March 28, 2020.

Boylan, Anne M. Women’s Rights in the United States: A History in Documents. NY: Oxford, a University Press, 2016.

“Excerpt from Dora Lewis letter to her daughter, Louise Lewis, Apr. 14, 1920, Dover, Delaware.” Pennsylvania Women and the Quest for Woman Suffrage. Historical Society of Pennsylvania. https://hsp.org/sites/default/files/attachments/pagesfromlewislettertodaughterapril141920extracted2.pdf. Accessed March 28, 2020.

“Five You Should Know: African American Suffragists.” National Museum of African-American History & Culture. https://nmaahc.si.edu/blog-post/five-you-should-know-african-american-suffragists. Accessed March 28, 2020.

Harley, Sharon. “African American Women and the Nineteenth Amendment.” National Public Radio. APRIL 10, 2019. https://www.nps.gov/articles/african-american-women-and-the-nineteenth-amendment.htm. Accessed March 28, 2020.

LeMay, Kate Clarke. Votes for Women! A Portrait of Persistence. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2019.

Mayo, Edith. “African American Women Leaders in the Suffrage Movement.” Turning Point Suffragist Memorial.https://suffragistmemorial.org/african-american-women-leaders-in-the-suffrage-movement. Accessed March 28, 2020.

Roberts, Rebecca Boggs. Suffragists in Washington, D.C.: The 1913 Parade and the Fight for the Vote. Charleston: The History Press, 2017.

“Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence.” Exhibit. National Portrait Gallery. Washington, D.C., November 17, 2019. Zimet, Susan, and Todd Haskell-Lowy. Roses and Radicals. NYC: Viking, 2018.